When news broke that Typhoon Tino (Kalmaegi) was heading toward the Visayas, residents wasted no time preparing. People tied down their roofs with ropes, stocked up on essential supplies, took out their generators and solar-powered devices, and kept their go-bags within reach.

Across the province, local government units also mobilized. Disaster risk management teams were activated, and emergency vehicles as well as personnel were placed on standby to monitor vulnerable areas. On paper, Cebu seemed ready.

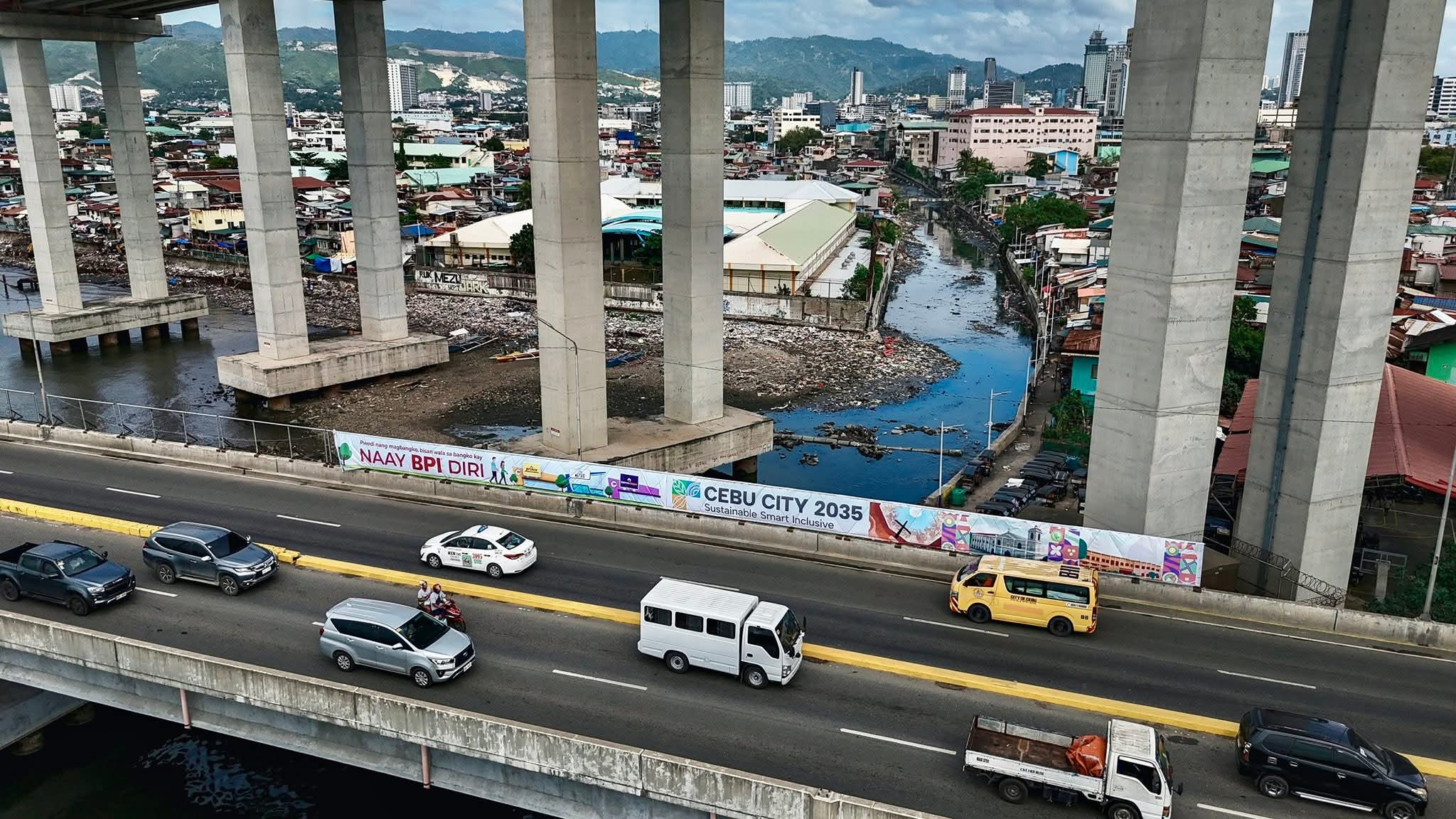

But as Typhoon Tino unleashed its fury, bringing torrential rains, fierce winds, and widespread flooding, the storm revealed painful weaknesses. Roads crumbled, power lines collapsed, rivers overflowed, and some flood control systems failed to withstand the effects of the typhoon.

In many areas, residents found themselves stranded, not because they were unprepared, but because the infrastructures meant to protect them, gave way.

Preparedness, as many are now realizing, is more than readiness at the household level; it must also be structural, systemic, and sustainable.

So the question now stands:

What happens to preparedness if infrastructures are not built to last?

Photo from Jacq Hernandez