The Goddess Through Time

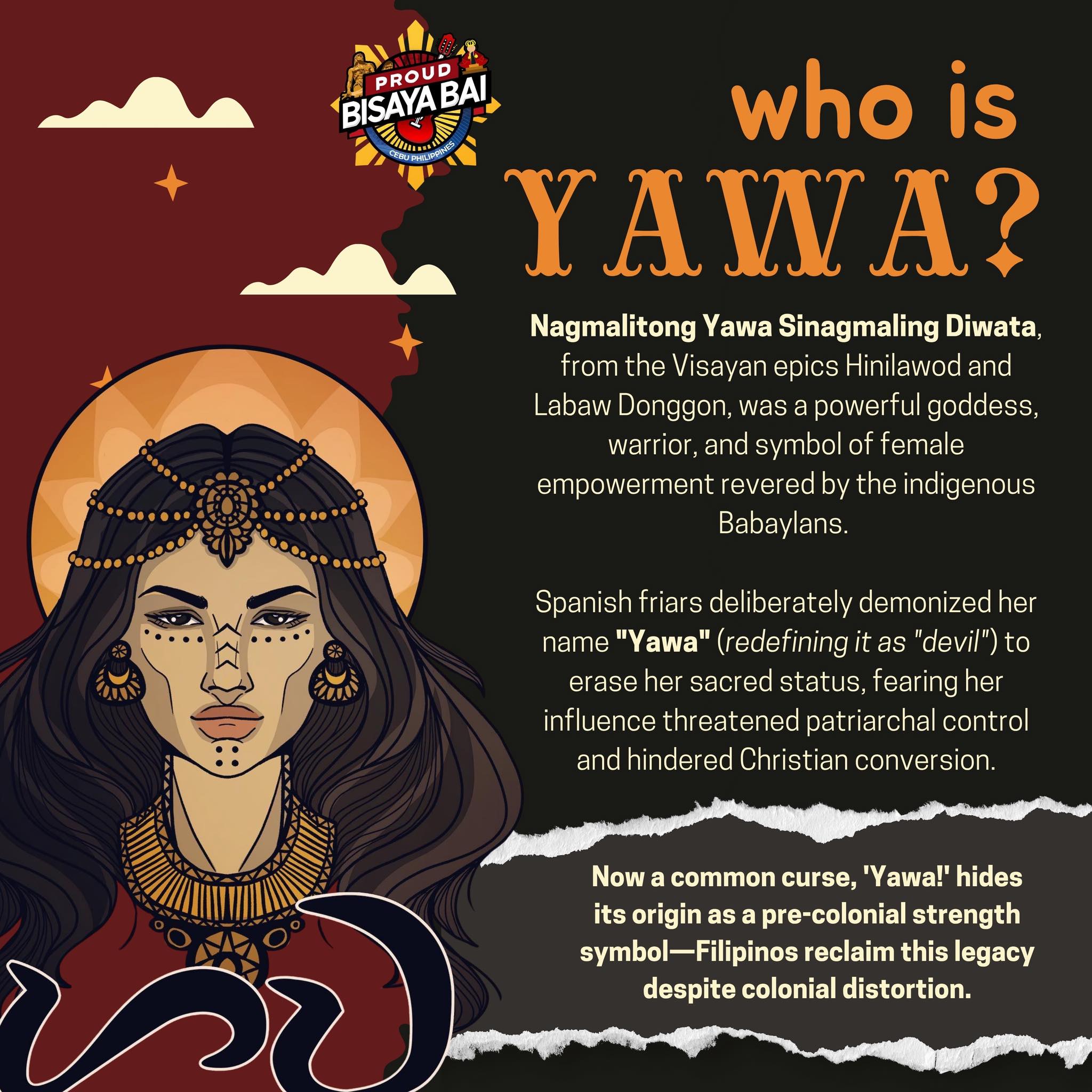

In Philippine mythology, few figures are as complex and misunderstood as Nagmalitong Yawa, a deity whose story has been shaped and reshaped by time, tradition, and transformation. Known by many names—Sinagmaling Diwata, the radiant goddess; Yawa, the divine temptress; and Nagmalitong Yawa, the dark enchantress—her narrative spans centuries of oral tradition, colonial influence, and modern reinterpretation.

This feature story explores the many versions of her story, from the ancient epics of the Visayas to the Spanish chronicles that sought to redefine her, and the contemporary efforts to reclaim her true significance.

The Spanish Colonial Tainting: A Name Distorted

When Spanish colonizers arrived in the Visayan islands in the 16th century, they brought with them not just swords and crosses, but a determined mission to erase indigenous beliefs and replace them with Catholic doctrine. The archives of early missionaries and colonists reveal a systematic pattern of demonizing local deities, and Nagmalitong Yawa was no exception.

The name “Yawa” itself became a victim of linguistic and cultural tainting by the Spanish authorities. Where indigenous peoples had understood Yawa as a powerful supernatural being, the Spanish deliberately transformed the term into “diablo” or devil, imposing their own moral framework on the Visayan spiritual world . This conscious rebranding of indigenous deities as evil spirits was part of a broader colonial strategy to undermine native spirituality and facilitate conversion to Christianity.

Friar Francisco Ignacio Alcina, one of the most detailed chroniclers of Visayan culture, documented this deliberate distortion in his 1668 work Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas. Though himself relatively respectful compared to his contemporaries, Alcina recorded the Spanish practice of mapping Visayan deities onto Christian concepts of good and evil, inevitably casting many once-revered figures as demonic.

The taint of sin and evil that came to surround Nagmalitong Yawa’s name reflects what scholars now recognize as a widespread colonial practice of mythological manipulation. By painting indigenous deities as wicked, the colonizers justified their suppression of local traditions and cemented their cultural dominance.

The Hinilawod Epic: Nagmalitong Yawa as Saragnayan’s Bride

The Hinilawod epic, one of the Philippines’ most significant oral traditions, presents perhaps the most famous narrative involving Nagmalitong Yawa. Discovered by anthropologist F. Landa Jocano in 1955 among the Suludnon people of Panay, Hinilawod (“Tales From The Mouth of The Halawod River”) offers a pre-colonial perspective that predates Spanish distortion.

In this sweeping epic, Nagmalitong Yawa appears as Sinagmaling Diwata, the breathtakingly beautiful wife of Saragnayan, the Lord of Darkness. Her radiance was said to be so brilliant that it illuminated the entire eastern sky, earning her the name “Sinagmaling” which translates to “radiant” or “brilliant.” She becomes the object of desire for Labaw Donggon, the arrogant but powerful son of the goddess Alunsina and the mortal Datu Paubari.

The epic recounts how Labaw Donggon journeys to the eastern sky to win Sinagmaling Diwata, challenging her husband to a duel that lasts for years. Saragnayan eventually defeats Labaw Donggon through mystical means and imprisons him beneath his house. The story continues with Labaw Donggon’s sons rescuing him, but only after Sinagmaling Diwata witnesses her husband’s defeat.

In this version, Nagmalitong Yawa is less an active protagonist than a prized possession fought over by powerful males—that reflects ancient Visayan social structures while also acknowledging female beauty as a powerful force. Notably, she exhibits no inherent evil in the Hinilawod account; rather, her perceived desirability becomes the catalyst for conflict among supernatural beings.

The Hinilawod epic was recognized for its cultural significance when it was inscribed in UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register in 2023, preserved at the Henry Luce III Library of Central Philippine University. This recognition highlights the importance of such indigenous narratives in understanding pre-colonial Philippine culture.

Alternative Mythology: The Malevolent Deity Version

Beyond the Hinilawod epic, alternative traditions present a strikingly different portrait of Nagmalitong Yawa—one where she embodies active malevolence rather than passive beauty. In these variations, often preserved in isolated indigenous communities or recovered from Spanish ecclesiastical records, she appears as a truly dark goddess with independent power and ambiguous morality.

In some regional traditions, Nagmalitong Yawa is recognized not merely as Saragnayan’s wife but as a powerful deity in her own right, associated with dark magic, temptation, and the dangerous aspects of desire. She is described as deliberately using her beauty to lure heroes to their doom, much like sirens in Greek mythology or succubi in Christian folklore.

This version aligns with what scholars term dystheism—the belief in or portrayal of a deity that is not wholly good, or even actively evil. Unlike the strictly benevolent gods of mainstream monotheism, dystheistic figures like Nagmalitong Yawa represent the complicated understanding of divinity in many indigenous traditions, where supernatural beings embody the full spectrum of moral qualities found in human experience.

In certain creation myths from the Visayas, Nagmalitong Yawa appears as a primordial being who existed before the current world order, associated with chaotic forces that the more orderly deities had to constrain. This interpretation resonates with patterns found throughout world mythology, where earlier divinities are often reimagined as demons or evil spirits by later religious traditions.

Some anthropologists suggest that these darker versions of Nagmalitong Yawa might represent pre-Hinilawod traditions that survived in isolated regions, possibly offering glimpses into more ancient Visayan beliefs that were later synthesized into the epic cycle where she appears primarily as Saragnayan’s beautiful wife.

The Spanish Justification: “Saving Souls” from a “Bad Deity”

The Spanish colonizers positioned themselves as saviors who were “doing the right thing” by suppressing indigenous beliefs, arguing that deities like Nagmalitong Yawa represented genuine evil that needed eradication. This narrative was carefully constructed to justify their colonial project and religious conversion efforts.

Spanish chroniclers described Nagmalitong Yawa as a “devil” or “evil spirit” who demanded human sacrifice and led people into temptation—claims that aligned with European witch-hunt ideologies but bore little resemblance to indigenous understandings. Friar Juan de Plasencia, in his 1589 work Costumbres de los Tagalos, explicitly categorized indigenous deities as manifestations of Satan, claiming the Spanish were saving Filipino souls from eternal damnation .

This colonial narrative argued that the babaylan (indigenous shamans) who worshipped Nagmalitong Yawa were “witches” consorting with dark forces. The Spanish pointed to practices like animal sacrifice, trance states, and spirit communication as evidence of demonic worship, ignoring their spiritual significance within indigenous culture.

The suppression was brutal: babaylans were persecuted, sacred objects destroyed, and indigenous rituals banned. Those who resisted were publicly whipped, humiliated, or executed as warnings to others. The Spanish documented these actions as necessary measures against “evil,” creating a historical record that framed colonization as a moral crusade.

Modern scholars now recognize this as a classic case of colonial propaganda—distorting indigenous beliefs to justify cultural eradication and political domination . The portrayal of Nagmalitong Yawa as inherently evil says more about Spanish anxieties than indigenous realities.

Modern Reclamation: Reinterpreting Nagmalitong Yawa Today

In contemporary Philippine culture, particularly among artists, scholars, and cultural activists, there has been a growing movement to reclaim and reinterpret mythological figures like Nagmalitong Yawa beyond colonial distortions and simplistic moral binaries.

Feminist scholars have particularly embraced Nagmalitong Yawa as a symbol of female power that was systematically suppressed by both colonial forces and indigenous patriarchal structures. They point to how her story reflects the historical constraint of female agency and the tendency to reduce powerful women to their physical appearance or relationship to men.

Modern literary and artistic representations have begun exploring Nagmalitong Yawa’s perspective—imagining her as an individual with her own desires, ambitions, and internal conflicts, rather than merely a plot device in male heroes’ journeys. These contemporary retellings often emphasize her agency and challenge the traditional narratives that frame her as either passive prize or evil temptress.

The recognition of Hinilawod by UNESCO has further stimulated interest in reexamining Nagmalitong Yawa’s story within its proper cultural context, free from the colonial lens that distorted so many indigenous traditions. This academic and cultural work represents part of a broader movement to decolonize Philippine history and rediscover pre-colonial worldviews on their own terms.

Comparative Mythology: Nagmalitong Yawa in Global Context

Placing Nagmalitong Yawa within the broader context of world mythology reveals striking parallels with other misunderstood or demonized female deities across cultures. Much like Lilith in Jewish tradition, Medusa in Greek mythology, or Kali in Hinduism, Nagmalitong Yawa represents the intricate archetype of the powerful feminine that often gets simplified or vilified in patriarchal descriptions.

These cross-cultural patterns suggest that the transformation of Nagmalitong Yawa’s character may reflect universal psychological and social dynamics rather than purely local developments. The tendency to split female divinity into virgin/whore or goddess/demon binaries appears across many cultures, often coinciding with shifts in social organization toward more patriarchal structures.

The recent scholarly interest in dystheism—the belief in or study of evil deities—has provided a valuable groundwork for understanding figures like Nagmalitong Yawa without imposing foreign moral judgments. This approach allows for a more nuanced appreciation of how different cultures conceptualize power, morality, and the divine.

Perhaps the most profound lesson from examining Nagmalitong Yawa’s many faces is the recognition that mythological figures, like the people who create and perpetuate them, contain multitudes. They can be both divine and demonic, victim and villain, passive object and powerful agent—sometimes simultaneously. Embracing this complexity allows for a richer understanding of both mythology and the human experience it seeks to explain.

As Philippine culture continues to rediscover and reinterpret its pre-colonial heritage, figures like Nagmalitong Yawa offer powerful opportunities to reconnect with ancestral worldviews while creating new meanings relevant to contemporary life. Her story, once threatened with extinction by colonial forces, now enjoys renewed interest and respect—a testament to the resilience of cultural memory and the power of myth.